- Home

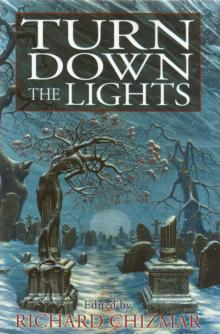

- Richard Chizmar (ed)

Turn Down the Lights

Turn Down the Lights Read online

Copyright © 2013 by Richard Chizmar

Individual stories Copyright © 2013 by their respective authors.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cemetery Dance Publications

132-B Industry Lane, Unit #7

Forest Hill, MD 21050

http://www.cemeterydance.com

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the authors.

First Trade Hardcover Printing

ISBN-13: 978-1-58767-437-2

Cover Artwork Copyright © 2013 by Alan M. Clark

Cover Artwork for Cemetery Dance #1 Copyright © 1988 by Bill Caughron

Cover Design by Desert Isle Design

Interior Design by Kate Freeman Design

For Billy and Noah,

my two favorite stories...

It was December 1988: George Bush had just defeated Michael Dukakis in the Presidential Election. Pitcher Orel Hershiser and the Los Angeles Dodgers had beaten the Oakland A’s in five games to win the World Series. People were waiting in line at movie theaters to watch Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man. Tom Clancy’s The Cardinal of the Kremlin and Anne Rice’s The Queen of the Damned were atop the bestseller lists. The most acclaimed genre books of the year were Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs and Peter Straub’s Koko.

I was 22 years old. And I decided to publish a magazine named Cemetery Dance.

At the time, I was studying journalism at the University of Maryland and selling short stories of a dark nature to any publication that would accept them. Some of these publications were professional and impressive. Many others, not so much. So—inspired by the brilliance of David Silva’s one-man magazine The Horror Show—I asked myself the question that has been responsible for most all of my crazier ideas: why not?

Why not dive right in and publish a magazine that showcased both seasoned pros and talented newcomers?

Why not publish the type of genre-blurring dark fiction I preferred to read and write myself: horror, suspense, crime.

Why not publish fiction alongside interviews and book reviews and genre commentary?

Why not open up to story submissions during summer break and schedule the premiere issue six months later in December?

Why not try to create something truly special?

The idea that I had no experience, no money, no business plan never really entered into the equation.

Dreams are for the courageous and the foolish. Cowards need not apply.

Why the hell not?

Did I mention I was 22 years old?

The premiere issue of Cemetery Dance was only 48 pages in length. It contained a dozen short stories, a dozen poems, an interview with David Silva, and cover and interior artwork by Bill Caughron. I should mention that Bill was my college roommate and childhood friend and the only guy I knew at the time who could draw. I can still remember him drawing interior spot illustrations right on the laser-printed pages of designed text. He drew the front cover sitting at our dining room table while I hurled darts over his head at a dartboard, nervously checking his progress every few minutes. I can also remember Bill and I hitting the PRINT button in the University of Maryland computer lab and running out of the room. You see, there was a very large sign posted above the printer that clearly stated: do not print more than 10 pages at a time. Laser printers were fairly slow back in those days, so suffice to say we were not very popular with the other students when we returned an hour later to collect our 96 pages. That’s right; we printed two copies. We were no dummies.

That first issue may have only run 48 pages, but it represented thousands of hours of work. Writing and mailing query letters. Making phone calls. Reading stories. Rejecting stories. Begging for stories. Trying to sell advertisements. Paying for advertisements in other publications to try to raise funds for printing. Designing interior pages. There was no guidebook. No roadmap except what existed inside my head. Almost everything came from instinct and imagination and passion. And making and learning from mistakes along the way.

Thankfully, I had Dave Silva to help me avoid some of those mistakes; he answered questions at all times of the day and night; he was a friend and a mentor. Encouraging me. Believing in me.

Still...for every success, there seemed to be a failure. Sometimes two or three. But I rarely felt discouraged or had doubts. I was having the time of my young life, and I sensed there was...something here. Maybe something special. I just had to keep working at it. I just had to keep believing.

The first issue was released right on time in December, and I remember we already had most of the second issue in the can. And R.C. Matheson lined up to feature in the third issue.

It was never a question of whether we would continue.

It was never a question of success or failure.

From the very beginning, it just was.

Why not, right?

When I realized that we were coming up on 25 years since that premiere issue was published I knew I wanted to do...something.

Something personal to mark the anniversary and the long journey we had all made together.

So much had happened in those 25 years: the magazine had spawned a hardcover book imprint...and trade paperbacks...and comics...and t-shirts...and electronic books...and cool things still to come.

And so much had happened in real life, too: marriage, two amazing children, the loss of my oldest sister, cancer, cancer again a year later, the loss of my parents.

In other words...life happened.

And, somehow, Cemetery Dance was there to witness all of it.

To be a part of all of it.

The book you hold in your hands is very personal to me.

In a way, it’s my own little celebration party 25 years later.

There is a reason it’s a small book. I wanted to include only the handful of writers who, in my mind, were as responsible for Cemetery Dance existing today as I am myself.

I won’t go into each individual writer. They know why they are here.

A few authors couldn’t make it because of their schedules—I only decided to put this together two weeks ago; why not, right?—although they each said they wanted to.

And, sadly, still another handful are missing. I wish Dave Silva were alive to appear in these pages. The same goes for Charlie Grant and Rick Hautala and Bill Relling. They all believed in me during those early days, and their faith meant so much.

It’s December 2013: I owe such a debt of gratitude to each and every person who ever lent their talents to the magazine; to an amazing full-time staff and a slew of part-timers; and to the wonderful readers who kept asking for more. I have no way to repay you other than to continue doing what I have been doing these past 25 years. I hope it’s enough.

Now, turn down the lights, flip the page, take my hand, and start the dance...

ROBINSON WAS OKAY AS LONG AS GANDALF WAS. NOT okay in the sense of everything is fine, but in the sense of getting along from day to day. He still woke up in the night, often with tears on his face from dreams—so vivid!—where Diana and Ellen were alive, but when he picked Gandalf up from the blankets in the corner where he slept and put him on the bed, he could more often than not go back to sleep again. As for Gandalf, he didn’t care where he slept, and if Robinson pulled him close, that was okay, too. It was warm, dry, and safe. He had been rescued. That was all Gandalf cared about.

With another living being to tak

e care of, things were better. Robinson drove to the country store five miles up Route 19 (Gandalf sitting in the pickup’s passenger seat, ears cocked, eyes bright) and got dog food. The store was abandoned, and of course it had been looted, but no one had taken the Eukanuba. After June Sixth, pets had been about the last thing on people’s minds. So Robinson deduced.

Otherwise, the two of them stayed by the lake. There was plenty of food in the pantry, and boxes of stuff downstairs. He had often joked about how Diana expected the apocalypse, but the joke turned out to be on him. Both of them, really, because Diana had surely never imagined that when the apocalypse came, she would be in Boston with their daughter, investigating the academic possibilities of Emerson College. Eating for one, the food would last longer than he did. Robinson had no doubt of that. Timlin said they were doomed.

If so, doom was beautiful. The weather was warm and cloudless. In the old days, Lake Pocomtuc would have buzzed with powerboats and jet-skis (which were killing the fish, the oldtimers grumbled), but this summer it was silent except for the loons...only there seemed to be fewer of them crying each night. At first Robinson thought this was just his imagination, which was as infected with grief as the rest of his thinking apparatus, but Timlin assured him it wasn’t.

“Haven’t you noticed that most of the woodland birds are already gone? No chickadee concerts in the morning, no crow-music at noon. By September, the loons will be as gone as the loons who did this. The fish will live a little longer, but eventually they’ll be gone, too. Like the deer, the rabbits, and the chipmunks.”

About such wildlife there could be no argument. Robinson had seen almost a dozen dead deer beside the lake road and more beside Route 19 on that one trip he and Gandalf had made to the Carson Corners General Store, where the sign out front—BUY YOUR VERMONT CHEESE & SYRUP HERE!—now lay facedown next to the dry gas pumps. But the greatest part of the animal holocaust was in the woods. When the wind was from the east, toward the lake rather than off it, the reek was tremendous. The warm days didn’t help, and Robinson wanted to know what had happened to nuclear winter.

“Oh, it’ll come,” said Timlin, sitting in his rocker and looking off into the dappled sunshine under the trees. “Earth is still absorbing the blow. Besides, we know from the last reports that the southern hemisphere—not to mention most of Asia—is socked in beneath what may turn out to be eternal cloud cover. Enjoy the sunshine while we’ve got it, Peter.”

As if he could enjoy anything. He and Diana had been talking about a trip to England—their first extended vacation since the honeymoon—once Ellen was settled in school.

Ellen, he thought. Who had just been recovering from the break-up with her first real boyfriend and was beginning to smile again.

On each of these fine late summer post-apocalypse days, Robinson clipped a leash to Gandalf’s collar (he had no idea what the dog’s name had been before June Sixth; the mutt had come with a collar from which only a State of Massachusetts vaccination tag hung), and they walked the two miles to the pricey enclave of which Howard Timlin was now the only resident.

Diana had once called that walk snapshot heaven. Much of it overlooked sheer drops to the lake and forty-mile views into New York. At one point, where the road buttonhooked sharply, a sign that read MIND YOUR DRIVING! had been posted. The summer kids of course called this hairpin Dead Man’s Curve.

Woodland Acres—private as well as pricey before the world ended—was a mile further on. The centerpiece was a fieldstone lodge that had featured a restaurant with a marvelous view, a five-star chef, and a “beer pantry” stocked with a thousand brands. (“Many of them undrinkable,” Timlin said. “Take it from me.”) Scattered around the main lodge, in various bosky dells, were two dozen picturesque “cottages,” some owned by major corporations before June Sixth put an end to corporations. Most of the cottages had still been empty on June Sixth, and in the crazy days that followed, the few people who were in residence fled for Canada, which was rumored to be radiation-free. That was when there was still gasoline to make flight possible.

The owners of Woodland Acres, George and Ellen Benson, had stayed. So had Timlin, who was divorced, had no children to mourn, and knew the Canada story was surely a fable. Then, in early July, the Bensons had swallowed pills and taken to their bed while listening to Beethoven on a battery-powered phonograph. Now it was just Timlin.

“All that you see is mine,” he had told Robinson, waving his arm grandly. “And someday, son, it will be yours.”

On these daily walks down to the Acres, Robinson’s grief and sense of dislocation eased a bit; sunshine was seductive. Gandalf sniffed at the bushes and tried to pee on every one. He barked bravely when he heard something in the woods, but always moved closer to Robinson. The leash was necessary only because of the dead squirrels and chipmunks. Gandalf didn’t want to pee on those; he wanted to roll in what was left of them.

Woodland Acres Lane split off from the camp road where Robinson now lived the single life. Once the lane had been gated to keep lookie-loos and wage-slave rabble such as himself out, but now the gate stood permanently open. The lane meandered for half a mile through forest where the slanting, dusty light seemed almost as old as the towering spruces and pines that filtered it, passed four tennis courts, skirted a putting green, and looped behind a barn where the trail horses now lay dead in their stalls. Timlin’s cottage was on the far side of the lodge—a modest dwelling with four bedrooms, four bathrooms, a hot tub, and its own sauna.

“Why did you need four bedrooms, if it’s just you?” Robinson asked him once.

“I don’t now and never did,” Timlin said, “but they all have four bedrooms. Except for Foxglove, Yarrow, and Lavender. They have five. Lavender also has an attached bowling alley. All mod cons. But when I came here as a kid with my family, we peed in a privy. True thing.”

Robinson and Gandalf usually found Timlin sitting in one of the rockers on the wide front porch of his cottage (Veronica), reading a book or listening to his iPod. Robinson would unclip the leash from Gandalf’s collar and the dog—just a mutt, no real recognizable breed except for the spaniel ears—raced up the steps to be made of. After a few strokes, Timlin would gently pull at the dog’s gray-white fur in various places, and when it remained rooted, he would always say the same thing: “Remarkable.”

On this fine day in mid-August, Gandalf only made a brief visit to Timlin’s rocker, sniffing at the man’s bare ankles before trotting back down the steps and into the woods. Timlin raised his hand to Robinson in the How gesture of an old-time movie Indian. Robinson returned the compliment.

“Want a beer?” Timlin asked. “They’re cool. I just dragged them out of the lake.”

“Would today’s tipple be Old Shitty or Green Mountain Dew?”

“Neither. There was a case of Budweiser in the storeroom. The King of Beers, as you may remember. I liberated it.”

“In that case, I’ll be happy to join you.”

Timlin got up with a grunt and went inside, rocking slightly from side to side. Arthritis had mounted a sneak attack on his hips, he had told Robinson, and, not content with that, had decided to lay claim to his ankles. Robinson had never asked, but judged Timlin to be in his mid-seventies. His slim body suggested a life of fitness, but fitness was now beginning to fail. Robinson himself had never felt physically better in his life, which was ironic considering how little he now had to live for. Timlin certainly didn’t need him, although he was congenial enough. As this preternaturally beautiful summer wound down, only Gandalf actually needed him. Which was okay, because for now, Gandalf was enough.

Just a boy and his dog, he thought.

Said dog had emerged from the woods in mid-June, thin and bedraggled, his coat snarled with burdocks and with a deep scratch across his snout. Robinson had been lying in the guest bedroom (he could not bear to sleep in the bed he had shared with Diana), sleepless with grief and depression, aware that he was edging closer and closer to just giving up and p

ulling the pin. He would have called such an action cowardly only weeks before, but had since come to recognize several undeniable facts. The pain would not stop. The grief would not stop. And, of course, his life was not apt to be a long one in any case. You only had to smell the decaying animals in the woods to know that.

He’d heard rattling sounds, and at first thought it might be a human being. Or a bear that had smelled his food. But the gennie was still running then, and the motion lights that illuminated the driveway had come on, and when he looked out the window he saw a little gray dog, alternately scratching at the door and then huddling on the porch. When Robinson opened the door, the dog at first backed away, ears back and tail tucked.

“You better come in,” Robinson had said. “If you can’t follow your nose, just follow the goddam mosquitoes.”

He gave the dog a bowl of water, which he lapped furiously, and then a can of Prudence corned beef hash, which he ate in five or six huge bites. When the dog finished, Robinson stroked him, hoping he wouldn’t be bitten. Instead of biting, the dog licked his hand.

“You’re Gandalf,” Robinson had said. “Gandalf the Grey.” And then burst into tears. He tried to tell himself he was being ridiculous, but he wasn’t. The dog was, after all, a living being. He was no longer alone in the house.

“What is the news about that motorcycle of yours?” Timlin asked.

They had progressed to their second beers. When Robinson finished his, he and Gandalf would make the two-mile trek back to the house. He didn’t want to wait too long; the mosquitoes got thicker when twilight came.

If Timlin’s right, he thought, the bloodsuckers will inherit the earth instead of the meek. If they can find any blood to suck, that is.

Turn Down the Lights

Turn Down the Lights